The last time I spoke with him on the record, the Big Eagle said it best. “Take the wings off, and give them an engine that sings.”

It’s an idea that is both obvious and familiar, yet totally revolutionary in the modern age of motorsports, which is precisely why it deserves a moment of our undivided attention. Dan Gurney didn’t make this statement haphazardly; he knew he was going to be asked what he thought about the future of the sport and had ample time to prepare a response. Other titans of our sport have voiced similar points of view. This project is a provocation to give the reasons behind those comments their due breathing space, and to steer the conversation beyond a simple thought experiment.

Dan’s point of view didn’t come from a desire to return to the past. He fundamentally looked ahead – perhaps better than anyone else in the history of the sport. It came from going through it and, later in life, having the space to zoom out. It came from knowing that the motorsports of today is a completely different animal than in any previous era. It came from a recognition that, yes, motorsports – mainstream motorsports in particular – is about entertainment; that its success revolves around evocatively engaging a broad and captive audience and generating a compelling reason to dig in and continue to follow. The key distinction lies in what the word “entertainment” really means.

To Dan, and to me, as a racer, a fan, and someone who cares deeply that this thing we have such passion for has a deeper meaning into the future than the weekend results alone, entertainment is not simply about how close the finish is, or how many cars are on the lead lap.The ultimate entertainment comes from witnessing humanity.

When we can tell that we’re witnessing a person doing something remarkable; when we can distinguish the style of one individual from another while recognizing greatness in both; when we intuitively understand the human experience on display, it creates a magnetic attraction that cuts deep. No amount of data or analytics can give you this feeling; you must be able to connect with these things using the naked eye.

And behold, the car itself – not in how it looks sitting still, but in how it dynamically behaves – is how this primal humanness is communicated to the audience. Horsepower, motion and yaw reveal it. Downforce, in contrast, suppresses it, and while we’ve spent the last 20 years reducing power outputs to contain outright speed over a lap while the unstoppable hum of science, engineering, technology and design continues its relentless march toward refinement, it’s spread like a virus across the entire motorsports landscape.

Downforce is not only masking the essential humanness that anchors motorsports’ very reason for being, but in a wild twist of fate it’s actually holding it back from safely going faster.

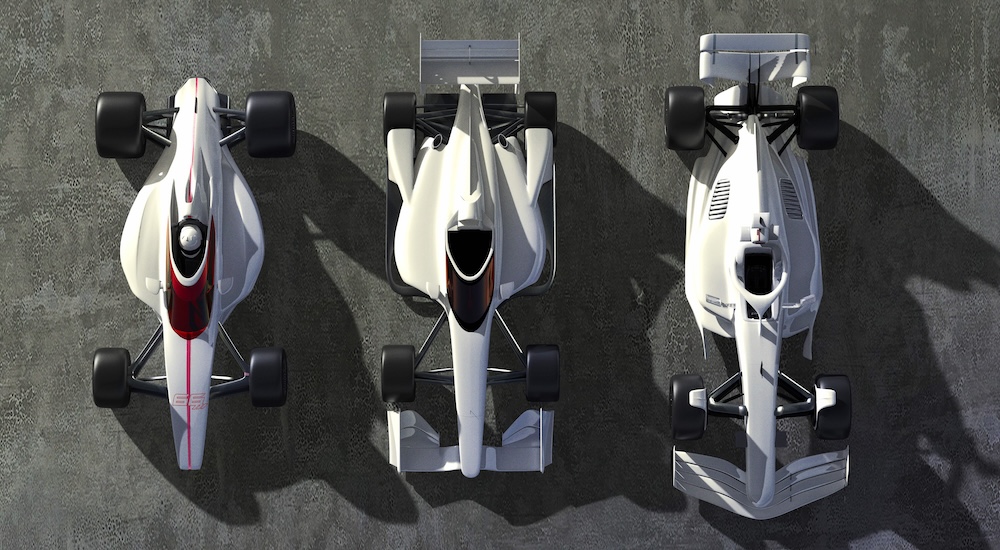

Wingless wonder… Stripping downforce from the Blackbird 66 Mk.1 – a lot of downforce – is central to the concept. All images: Patrick Faulwetter

So while I’ve got your attention, let’s dig a little deeper. And this design project is an excuse to do exactly that. I’ll put some data behind the what and the why, and hopefully inspire this conversation to continue beyond these pages alone.

Here’s a basic truth: the margin between how top-tier mainstream racecars currently perform and how fast they could be is at an all-time high. Save for, let’s say, Can-Am, Group B rally cars, and the early ’90s version of GTP – all regulated with such a degree of openness that the margin between what was actually on track and what was possible with no rulebook whatsoever was razor-thin – the gap between regulated performance and potential performance has always existed in racing as we know it. But that gap has grown. As noted above, most all of mainstream motorsports has been up against a particularly rigid artificial barrier from going faster for more than two decades on the grounds of safety, while the science and technology that dictates what could be happening continues to advance.

But that’s not what I’m interested in discussing. Instead, it’s what it means for how we can move forward, which is simply this: we have more options than ever, and they deserve to be explored.

In any given mainstream motorsports vehicle formula, there’s some combination of weight, size, general shape and dimensions, mechanical grip via chassis and tires, power output, and downforce and drag. But few, if any, of these sliders are maxed out. In fact, there’s so much room to play on so many of these sliders that even radical changes would have little to no impact on the difficulty or expense of design, engineering or operations. Consider even Formula 1 – undoubtedly the pinnacle of technology, engineering, and performance across the sport. How much more power would F1 cars generate if you just gave them all an extra liter of engine displacement to play with?

I’m a believer in the idea that in order to really understand the domain of your problem, you must explore the extreme edges of it. I’m also a believer in the idea that if you’re to produce something truly compelling, it needs to be sufficiently radical. We know that motorsports has lost some of its primal magic due to an over-downforcification and refinement of the basic vehicle formulas we use. We know there are safety implications to exceeding a certain degree of outright speed, specifically on the grounds of containing high-speed crash energies. We know that there’s now ample room to move the vehicle formula sliders around in a variety of directions and magnitudes.

In the end, we must acknowledge that we’re not just guiding the same old ship; we are making a choice, and there’s a lot to choose from. How radical could you get while still producing something viable within modern constraints? This is the conversation I’m here to have, and the basis for the Mk.1 project you see here.

I want to know two things: how excessively evocative can we make the driving/viewing experience, and how fast can we go with a formula that’s built for that? The answer to both is very, and we shouldn’t shy away from that. Let’s use a very general comparison between the current IndyCar and the current F1 car as a basis for this discussion. At COTA in 2019, these two formulas produced lap times roughly 13 percent apart, so for the sake of the thought experiment, let’s first consider how we could bridge that gap as a means of understanding a few sensitivities.

On a road or street circuit, a 20 percent increase in power is worth something like a 2-2.5 percent increase in lap speed. A 10 percent increase in tire grip – softer or bigger tires – is worth something like 2-2.5 percent as well. A 10 percent reduction in weight also has roughly a 2-2.5 percent effect. So, from its pre-hybrid 2019 spec, make the IndyCar ~850hp, reduce its weight by ~200lbs and increase its tire size by 10 percent and you’re already halfway there.

Now let’s reduce the weight again, because a non-hybrid IndyCar that weighs 1,600lbs is not absurd at all. This was the DW12 chassis’ original weight. That’s another 2-2.5 percent. Add power, 2-2.5 percent. Then add some more. 2-2.5 percent. Yes, I’m talking four digits and then some for qualifying trim. Honda, Chevy, Cosworth, anybody could make this reality, they just need their hands untied. We’re now talking about something that, in all likelihood, is faster – possibly by a chunk – than a contemporary F1 car, without doing anything revolutionary.

That’s exciting, but still isn’t the point, because speed alone isn’t the goal. Speed alone has consequences that I don’t want. Have we achieved the most excessively evocative version of this make-believe vehicle? No, not yet. It’s got the juice, now for the squeeze.