When a pack of Formula 5000 cars bellowed into life on Friday, Sept. 26, 1975, somewhere around 1:15pm PT, then rumbled out of the pits to embark on their 80-second, 90mph route around the streets of downtown Long Beach, it was the penultimate step in a dream sequence initiated, devised and delivered by California-based Englishman, Chris Pook.

The growl of those 302cu.in Chevys (and a couple of Dodges) rattled the glass of pawnshops and (somewhat disguised) porn shops, and by the end of Sunday, a run-down Southern California city whose main claims to fame had been harboring a 40-year-old ocean liner and building brand-new airliners now also had itself an auto race. This noisy curio, not quite in the shadow of the Queen Mary and not quite under the flightpath of McDonnell Douglas, attracted 65,000 people over the three days, according to the media. And this was a mere curtain-raiser. In six months, the same temporary track would host the third round of the 1976 Formula 1 World Championship.

Pook had moved to Southern California in 1963, and by ’73 was a high-flying travel agent, with the accounts of the San Diego Chargers, California (now LA) Angels, Oakland Athletics and LA Sharks sports franchises. And when he also landed the account for the Long Beach Convention and Visitors Bureau (LBCVB), he swiftly learned that the city was in need of a major boost.

“Long Beach was in trouble in the late ’60s and early ’70s,” says Pook (above). “Having lost its oil revenues, it decided to become a tourist and convention destination. The problem was that it had no decent quality hotels. It had motels for the Navy and ship-building boys, but that was it.

“I said to the LBCVB guys, ‘It’s going to take you years to establish this as a trade show and convention area. You’re a hidden destination.’ They agreed and asked what could be done, and I said, ‘You need to do something outrageous like Monte Carlo did to compete with Nice and Cannes: they came up with the Monaco Grand Prix. Why don’t you just copy them?!’ And the long and the short of it, that’s how the race came about.”

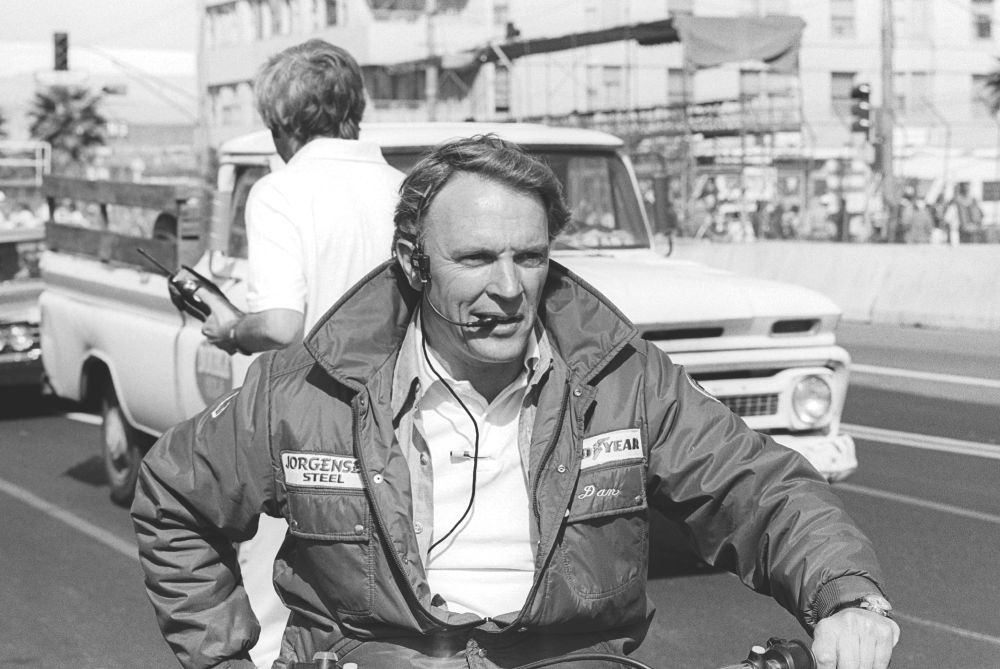

If that was a wild idea, Pook was also a realist: to get people even v aguely interested, he would need support from someone with the credibility and status to make skeptics listen. So he approached Dan Gurney, only recently retired from driving and neck-deep in team ownership and overseeing engineering at his All American Racers outfit. Pook couldn’t have picked a more suitable figure: of course the ever-adventurous Dan was intrigued by the idea of a SoCal street race.

A chapter of Gurney’s as yet unpublished autobiography, “The Passion of Former Days,” written with his wife Evi, is dedicated to the Grand Prix of Long Beach’s origins. The late legend recalled telling Pook, “It’s bold, it’s risky, it will probably never happen, but I like it, I like it a lot. Damn the torpedoes, let’s go full steam ahead like in the pioneer days!”

He went on: “I asked for a legal opinion from my attorneys… They wrote a letter back, outlining the pros and cons, ending with the sentence, ‘Considering all the facts, we cannot recommend your involvement.’ Evi has reminded me through the years that I read this letter to her in my office, then tore it up…while lamenting the lack of courage, vision and pioneering spirit in our country.

“To me, a race through a city was not a lunatic idea as some characterized it, but maybe exactly the right and innovative thing to shake up the establishment and capture the hearts and imagination of racing fans worldwide. We were businessmen, but we still had a soul and a bit of romanticism in our DNA. To try and create something against all odds appealed to my nature.”

Gurney was so enthusiastic that on his and Pook’s first meeting with the LBCVB, he designed the course, which they later drove to confirm its viability.

Wrote Gurney: “Considering the layout of the city, it was very important in my view to make Ocean Blvd. the long main straight of the circuit. We’d make the two shorter sections downhill on Linden and uphill on Pine Street part of the track as well. These two sections proved to be spectacular, praised by drivers and spectators alike. To see an F1 car racing there at speed, sliding sideways down the hill, remains etched in my memory as an unforgettable experience.”

Gurney would recruit Les Richter, the former LA Rams linebacker who’d been running Riverside International Raceway since 1959, to provide advice and impetus when tackling city councilors, who were initially among the skeptics. But Pook really started to believe the event was going to happen when Gurney got Tom Binford onboard.

“Tom was chairman of ACCUS ,” says Pook, “and they were the liaison between the FIA and the U.S. racing scene. He came out here with Dr. Nino Bacciagaluppi, who was operations director at Monza and chairman of the safety commission; when they got excited, the project really gained momentum. That was the summer of ’74. I’m not saying all the hurdles had been jumped and all the red tape cut through, but that was when it really felt we had the right people on our side.”

One of those hurdles was that new F1 tracks needed to be at least 2.5 miles long, and Gurney’s Long Beach layout for Long Beach was 2.02 miles, but Monaco, too, was barely more than two miles in length, which cooled that potential hot potato.

Also, any new track on the F1 calendar needed to be proven viable by running another professional race beforehand. Again, no problem: both the SCCA and USAC were supportive, and their headline act, F5000, would prove ideal as a headliner in ’75. Then, in late ’74, Gurney drove one of his F5000 Eagles up a closed stretch of Shoreline Drive to pass the decibel test. All good.