There are three names in the lexicon of auto racing greatness that are forever bound together in history and only require a first name for identification: A.J., Mario and Parnelli.

Throw in Dan Gurney and you have the four most versatile, decorated and revered racers in our lifetime.

Now, when you consider that Rufus “Parnelli” Jones only made seven starts in the Indianapolis 500, is tied with Roscoe Sarles and Bob Burman for 59th on the all-time Indy car win list with just six, and walked away from the big stage at age 34, a younger fan might wonder why he’s even in the Mount Rushmore conversation. After all, he wasn’t a four-time Indy winner, a Formula 1 champ or a globetrotting hero.

But, in fact, he was a monstrous talent – fast, smooth and smart – who mastered anything with four wheels, on dirt or pavement. And some pretty good judges think Rufus may have been the best all-’round driver ever.

“I know he was my hero but, in my eyes, Parnelli was the greatest,” declared three-time Indy 500 winner Bobby Unser.

“When things were right during that period, nobody could beat him. Nobody. He was The Man,” said Mario Andretti.

“I would rank A.J. first and Parnelli a strong second, if not tied for first,” said Johnny Rutherford.

“He was one of the special few who you always had to contend with and always had to work up a sweat to beat,” said Gurney.

Of course, it was Indianapolis Motor Speedway that cemented Jones into the pantheon of greatness.

“For my money, he was the best who ever ran Indianapolis,” said A.J. Watson.

Now, before you dismiss Watson as a crazy old man, since Parnelli won only one Indy 500 and 20 other drivers have multiple victories, feast on these stats and facts:

• He led 492 laps in his seven starts at the Speedway, which is eighth on the IMS chart and more than four-time winners Rick Mears and Helio Castroneves, or three-timers Dario Franchitti and Bobby Unser.

• In 1961, as a rookie, he passed three cars in one fell swoop to take the lead and was comfortably out in front and pulling away when he lost a cylinder.

• In 1962, after breaking the 150mph barrier in qualifying to win the pole, he led 120 laps, but lost his brakes and faded to seventh.

• In 1963, he led 167 laps en route to his lone victory at the Brickyard.

• In 1964, he was dueling for the lead when he came into the pits and his car caught fire and he was KO’d again.

• In the 1965 race, he finished second to Jimmy Clark’s Lotus 38.

• In the 1967 “500,” he was long gone in the controversial, turbine-powered STP-Paxton Turbocar when it broke down just four laps from victory.

So, other than Clark’s dominance in 1965, and 1966 when his Shrike-Offy wasn’t up to snuff, Jones could easily have won four other times. “Parnelli should have been the first five-time winner; he just had horrible luck,” said four-time Indy 500 king Al Unser, who scored two of his victories driving for Jones in 1970 and ’71.

In 1960, after smashing the IMS track record, rookie Jim Hurtubise issued a warning while being interviewed on the public address system. “If you think I’m good, wait until you see my buddy Parnelli.”

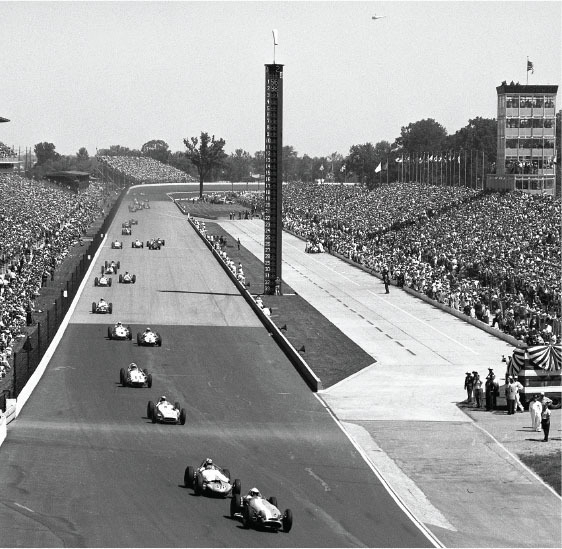

Tires, fuel and a gulp of water for Parnelli Jones on the way to his 1963 Indy 500 victory.

Thanks to watching Hurtubise dirt-track his way around the Brickyard in 1960 and endless miles of Firestone testing in ’60 and ’61, Jones figured out how to run those long, heavy, front-engine roadsters loose. Most veterans considered that suicidal, but one rookie had a different view.