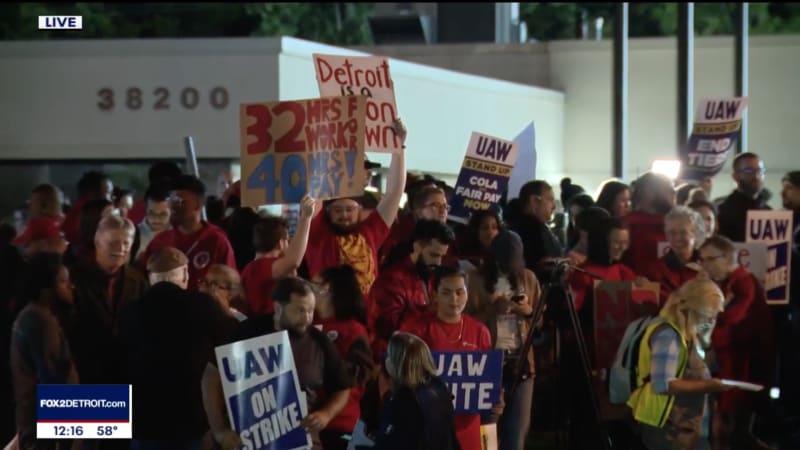

For the first time since 2019, the United Auto Workers union has gone on strike after failing to reach a deal with the three Detroit-based automakers. This strike is different from every other strike of the past, though. Never before in the UAW’s 80-plus-year history has the union ordered a strike on all three major American automakers at the same time, but that’s exactly what is happening now. It’s also the first time that the union has chosen to directly target specific plants in order to “cause confusion” — in UAW President Shawn Fain’s words — at the three automakers’ headquarters.

“For the first time in our history we will strike all three of the Big Three,” Fain said.

At present, there’s no way of knowing how long this strike will last, or how many plants will be affected before it’s all said and done. So far, the walkout is being kept to a few select manufacturing plants, but Fain has indicated that the number of striking workers and the plants affected will escalate as negotiation drags on.

Surrealistically, the strike begins as the Detroit Auto Show opens to the public.

On Strike at the Big Three. Stand Up Strike.

Support the strikers. Grab a support graphic for your timeline.#StandUpUAW #OnStrike #StandUpStrike pic.twitter.com/GGIpAeTVzd

— UAW (@UAW) September 15, 2023

Fain appeared at Ford’s Michigan Assembly plant early Friday to address UAW members and join the picket line. Speaking to reporters, Fain said addressed a claim from Stellantis that the union had not made serious counteroffers. Fain said the companies had the UAW demands for as long as five weeks. “We made counter-offers tonight,” Fain told reporters, saying the union had to file unfair labor practice claims to get two companies to the table. “It’s their fault. They waited till the last minute,” he said. “This is on them.”

“This isn’t just about the UAW,” said. “This is about working people everywhere.”

“We’re going to be out here until we get our share of economic justice, and it doesn’t matter how long it takes.”

“America is better than this.”

What plants are being targeted initially?

In a livestreamed video address Thursday night, two hours before the strike deadline, the union president described a strategy he termed a “stand-up strike.” He called on locals at three facilities to stand up and strike, one location per automaker. The targets are:

The strikes at those locations involve a combined 12,700 workers.

Fain vowed to walk the picket line at midnight with local members at Michigan Assembly. Workers at other plants will remain on the job in the meantime. Fain assured them that though the union contracts expired at midnight, those workers are still protected.

The strategy targets facilities that make popular and highly profitable models, but it initially could be considered something of a warning shot. Spared for now are facilities more central to automakers’ operations and bottom line, such as Ford’s River Rouge facility, which manufactures the F-150 and F-150 Lightning.

The strategy may well also serve to stretch the union’s strike fund, which is $825 million.

If a strike lingers, other units/facilities could be called into play, Fain said, perhaps expanding to a full strike across all three companies.

“This strategy will keep the companies guessing,” he said. “All options remain on the table.

“If we need to go all out, we will.”

Why did the UAW order a strike?

Put simply, negotiators for the UAW and their counterparts from Ford, General Motors and Stellantis (parent company of brands that include Chrysler, Dodge, Jeep and Ram) did not come to a satisfactory agreement ahead of 11:59 p.m. Thursday, September 14. That’s the day that the previous contract between the union and the automakers ended.

What is the UAW asking for?

Quite a bit. According to UAW President Fain, “Record profits mean record contracts.” According to the UAW, “Ford, General Motors and Stellantis made a combined $21 billion in profits in just the first six months of this year. That’s on top of the quarter-trillion dollars in North American profits that the Big Three made over the last decade.” The UAW calculates that if each of its 150,000 members received a $20,000 raise out of that $21 billion, the automakers would still have $18 billion of it left.